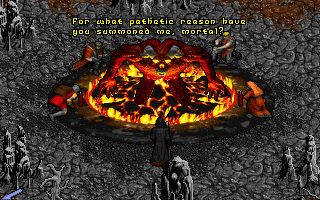

‘Breath of Fire II’ 1994

The original ‘Breath of Fire’ game was developed by Capcom for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System and was the work of designer Yoshinori Kawano (who was credited as Botunori) and producer Tokuro Fujiwara (creator of the ‘Ghosts ‘n Goblins’ series). Capcom’s head of development, Keiji Inafune, was at first placed onto the project and designed the game’s characters, however, Capcom later replaced him with Tatsuya Yoshikawa to free him to work on another title. Whilst ‘Breath of Fire’ is a quality game, it does fall into the trap of being extremely formulaic for the time of its release and failed to create a substantial or meaningful impact on the genre. In many ways Capcom was ticking genre boxes in its catalogue, ensuring that they had an RPG to cater to fans of the genre but not giving it their whole attention, as was evidenced by their removal of Inafune from the project mid-development. Its sequel however was a vast improvement.

Breath of Fire II was developed by the majority of the same Capcom employees who worked on the original game, including Fujiwara and Kawano. Taksuya Yoshikawa was also brought back onboard and given full artistic control of the project rather than being left to handle promotional art based on another artist’s designs. Where the original title had been handed to Square Soft in order for a translation to be completed and international release handled, Capcom USA managed the game in-house. This had hurt the original game, as Square had done an adequate but un-loved translation for the west in order to concentrate on their own games scheduled for release. A longer translation period by the same developer insured that more of the games story was faithfully retained abroad.

Set 500 years after the original game in a fantasy world, the story centres on a young man named Ryu. A strange series of events in his childhood that cumulates with an encounter with a dragon leads to Ryu having been seemingly written out of existence, the people of his home town unable to remember him and his family missing. Raised as an orphan with best friend and half-dog ‘Bow’ the pair sneak away to the big city in the hope of living there as thieves. A chance encounter with a winged maiden, Ryu’s connection to the power of dragons and the recognition by demons as a ‘Destined Child’ all feed into the evolving narrative and cumulate in one of two endings depending on how the player has done.

Unlike the original title, which employed a graphics based menu system that players had to navigate, the sequel includes a text-based menu similar to those seen in other games of the period. Each character the player recruits to the party brings with them a unique skill called a Personal Action that can be performed outside of combat and these range from helping negotiate the environment to destroying certain objects in the game world. A town-building mechanic was also included that sees the player hiring carpenters to build houses in the hopes of attracting Shamans to live there. These can be fused with party members to grant them evolved forms and abilities which adds a large amount of replay value.

Released for the SNES in the same week that Sony debuted their Playstation console in Japan, Breath of Fire II became the seventh highest-selling game in its first week, shifting 89,700 copies. By the end of 1995 the game would sell an additional 350,000 copies and would see a re-release in 1997 as a discount value game. Like ‘Breath of Fire’, the game would also receive a port to the Game Boy Advance in 2002 featuring redrawn graphics and the battle interface from ‘Breath of Fire IV’. A dash button would also be added to speed up play and link-cable functionality was added for trading items between cartridges. ‘Breath of Fire III’ would follow in 1997 for the Playstation, and ‘Breath of Fire IV’ would be released in 2000 for the same console. The series briefly took a hiatus after ‘Breath of Fire V: Dragon Quarter’ was poorly received on the Playstation 2, however confirmation of a sixth game being in development for mobile devices was announced in 2013.

‘Earthbound’ 1994

Known as ‘Mother 2’ in Japan, Earthbound was co-developed by Ape (later to be renamed Creatures) and Hal Laboratory and underwent a protracted development period of 5 years. After the release of ‘Mother’ on the NES in 1989 the games writer and designer (an author, musician and advertisement specialist) Shigesato Itoi started work on a sequel. Satoru Iwata, who would later become Nintendo’s president and CEO produced the original game and was vocal in his agreement that a sequel should be made, returning to produce the project.

Aside from these two individuals the sequel would use a different production team, picked in part because they were unmarried and willing to work through the night on the project, which had been a recurring problem with the original. Satoru Iwata and Kouji Malta programmed the title whilst artist Kouichi Ooyama produced sprites and illustrative work. Composers Keiichi Suzuki and Hirokazu Tanaka rounded out the team with designer Akihiko Miura. Although the group were unattached and dedicated to release, the games development took much longer than anticipated and came under repeated threat of cancellation.

Initially designed to fit a strict 8 megabits limit, the game expanded in scope twice over the course of its duration with first a shift to 12 and the 24 megabits. Scheduled for a release in January 1993, it was instead pushed back to August 1994 to accommodate the changes with the last few months of development spent adding fine detail and personal touches to the title from the development team. Shigeru Miyamoto would later go on record to state that it was the first RPG he’d ever completed. The game used a specific HP system where damage would roll back in the format of a counter rather than have digits subtracted from a total immediately. This allowed for even moves that would kill a character to be reversed if the player could heal the damaged party member before the counter finished counting down, adding an additional layer of strategy to proceedings. The games’ final boss encounter was based in part on imagery from a horror film that Itoi had seen in his childhood by accident and featured a flickering series of images in the background that a member of the team spent a year working on 200 animations for. Dialogue in game was written in Japanese kana script to allow for a more accessible and conversation tone than other titles at the time.

The only game in the Mother series to be translated and released in the west, ‘Mother 2’ was retitled ‘Earthbound’ to avoid questions as to why the original game had not seen release and Dan Owsen began work on translating the dialogue. Shortly into the project he was replaced by Marcus Lindblom, who although taking liberties with the script worked closely with a Japanese writer to mirror the tone and themes whilst giving the game a more American tone. Nintendo dictated that references to religion, alcohol and brand logos were removed and one series of characters was visually changed to avoid connections with the Ku Klux Klan. Spending 2 million dollars on marketing the American release was ultimately viewed as unsuccessful and magazines criticized the simple graphical style in a period where games were becoming more visually complex. The title’s later re-release onto the Virtual Console in 2013 was greeted with a much higher level of praise and it was stated by Lindblom that with hindsight the games graphics have aged extremely well. Whilst never selling well at launch the game has amassed a cult following who regularly petition Nintendo for the western release of more Mother titles.

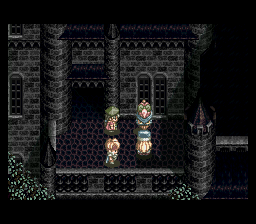

‘Final Fantasy VI’ 1994

After the release of ‘Final Fantasy V’ in 1992, Final Fantasy VI entered development. Series creator Hironobu Sakaguchi was unable to be as intimately involved in the development of the sixth instalment into his ground-breaking series due to pre-existing commitments to other projects (see ‘Chrono Trigger’ below) and his recent promotion into the position of Executive Vice President at Square in 1991. Assuming the role of producer, he split director responsibilities between Yoshinori Kitase (who had worked on ‘Final Fantasy Adventure’ and ‘Romancing SaGa’) and Hiroyuki Ito (who had been with Final Fantasy since its initial instalment).

The guiding principle behind Final Fantasy VI is that every character is the protagonist. Every member of the development team was tasked with submitting ideas for characters and their ‘episodes’ within the larger narrative. It was then left to Kitase to stitch these into the story outline written for the game by Sakaguchi and conceive a cohesive narrative. Kitase submitted elements of the opera scene and Celes’ suicide attempt as well as all of Kefka’s appearances, turning these into pivotal moments within the game. The opera scene in particular would be remembered as one of gaming’s most iconic moments.

Series regular character designer Amano developed concept art which later would be introduced to the games dialogue and menus in subsequent releases and was used as reference for CGI rendered cutscenes for the games Playstation re-release. Unlike previous games in the series, where sprites appeared in less detail on the map and were rendered with more complex sprites in battles, Final Fantasy VI uses the same, larger sprites throughout its length. Mode 7 graphics were employed at various points throughout the title, such as when using the airship or chocobo to tour the world map and at key events such as travelling underwater.

The western release of the game was graphically altered to remove nudity from some character models in keeping with Nintendo’s policies at the time and altered again (slightly less so) for release in Europe. Several small changes were also made to the English script. Ted Woolsey used several alternate phrases for swearing or overly violent actions, such as ‘Son of a bitch!’ becoming ‘Son of a submariner!’ lightening the tone. The character of Tina was also renamed Terra and some dialogue was cut to make space on screen for the change from Japanese to English. Interestingly, editions of the game later than the Playstation port have all cut a sequence in which Celes is being tortured by guards, even though the scene remains the action of being beaten is removed, lessening the heightened emotion at that point in the game in favour of lessening the adult tone.

Released as ‘Final Fantasy III’ in the west due to entries being skipped and released only in Japan, the game remains III on its Virtual Console edition, which emulates a SNES despite the fact that subsequent re-releases have it correctly numbered. The game has seen re-releases on Playstation, Game Boy Advance, Virtual Console, Playstation Network, Android and iOS to date and was launched to critical acclaim in Japan, selling over 2.55 million units to date and became the eighth best-selling title of any kind in the west in 1994.

‘Shadowrun’ 1994

Based on a cyberpunk-fantasy hybrid pen and paper roleplaying setting of the same name, Shadowrun was developed by the Australian company Beam Software and was released in 1993 for the SNES by Data East. The narrative loosely follows that of the novel ‘Never Deal with a Dragon’ by Shadowrun co-creator Robert N. Charrette and was later linked with the game of the same name on the Mega Drive by the narrative of Shadowrun Returns in 2003.

Development began on the game when Adam Lanceman, a member of the company’s management team acquired the license for Shadowrun from its publisher FASA. The project was initially headed by Gregg Barnett, however he abruptly quit working for Beam Software during development in order to start the company Perfect Entertainment in the United Kingdom. Due to his absence the game was stalled and production halted, however it was eventually reinstated in order to meet its deadline due to Beam having already paid to advertise it and secure the license. Paul Kidd was hired to replace Barnett, who had a strong fantasy and science fiction background as a writer and was already familiar with the license because he was an avid roleplayer. Initially wanting to pitch his own story within the setting, ultimately time constraints from Data East led to him keeping the original plot outline but added more film noir influences and tone as well as numerous dialogue heavy exchanges to better suit his experience of the setting. More humorous moments were also added to lighten the mood in an overall downbeat story. Kidd described this as “making improvements and changes” but the basic concepts were largely the same.

Two versions of the game were put forward. One containing adult tone and dialogue such as violent phrases and sexually suggestive NPCs, the other more Nintendo friendly. Data East chose to produce the lighter version, which replaced terms like ‘chop shop’ with ‘morgue’ and cut many of the aspects of the game that could be considered adult. Kidd was angered by this at the time, feeling that they weren’t paying the license its due and stating in an interview later that “Beam Software was a madhouse, a cesspit of bad karma and evil vibes.” He also commented that “old school creators who just wanted to make good games were being crushed down by a wave of managerial bull. It was no longer a ‘creative partnership’ in any way; it was ‘us’ and ‘them’. People were feeling creatively and emotionally divorced from their projects.” He credited the hard work of his team and staff at the time however and returned to writing novels not long after.

Shadowrun was released alongside two games using the same license; one for the Sega Mega Drive produced by BlueSky Software and another for the Mega CD produced by Compile. Whilst all three used the name ‘Shadowrun’ the storyline and gameplay of each was highly individual. When FASA founder Jordan Weisman announced the series’ return to the video game format with ‘Shadowrun Returns’ the protagonist of this title (Jake) was featured as a part of the new games storyline and temporary party member. Storylines from the SNES and Mega Drive titles were referenced throughout, consolidating them into a single timeline.

Shadowrun remains a rare exception of a tabletop RPG property other than Dungeons and Dragons spawning a successful video game series. ‘Shadowrun Returns’ was quickly followed by expansions ‘Dragonfall’ and ‘Hong Kong’ along with shooter ‘Shadowrun Chronicles: Boston Lockdown’.

‘Ultima VIII: Pagan’ 1994

After the release of ‘Ultima VII’ and its two expansion packs, Richard Garriott felt that he had created the definitive entry into his Ultima universe. Unfortunately having left the series on a cliff-hanger at the conclusion of VII and Origin Systems facing increasing pressure from their new owner, Electronic Arts, he was unable to close the book on Ultima.

Pagan picks up where the ‘Serpent Isle’ ended, with the Guardian grasping the Avatar from within the void and dropping him into the sea in a new land called Pagan. Unable to return to Britannia or Earth, the Avatar must negotiate this dark new environment which is more hostile than anything he’s ever encountered before. The games object is simply to escape Pagan, which Garriott describes thusly: “With Ultima VIII, I wanted to be even more severe with the sinister elements. That’s where your character went off to the land of Pagan, which was the Guardian’s home world. This world wasn’t your standard, virtuous goody-goody-two-shoes setting, to the point where if you tried to uphold the goody-goody-two-shoes life in the game, you couldn’t get anywhere. The challenge was that you had to stay true to your core personal beliefs without totally ransacking the place to achieve your ends and work with the system that was there. The storyline is basically one of those “sometimes you have to fight fire with fire” stories where, when you’re faced with true evil, you’ve got to cheat in order to win.”

Tonally, Pagan is a very different game in the series with audio-visual work at the forefront of design and a more cinematic tone than previously achieved. A return to form in many ways to the original trilogy, the game features hack and slash combat and a more arcade-like tone than later games in the series. Clever changes such as a new magic system due to the change to a new environment with its own rules and using the latest sound cards to make environments more vibrant bring the game to life, with the scenario’s high-concept storytelling at its core. Usually the Avatar is charged with doing only good, but the morally grey area of possibly harming others in order to achieve a greater good and murdering the perceived gods of others because you perceive them as evil makes the game an on-going series of debates and questionable choices. In this manner is achieves everything it sets out to do.

Facing a strict deadline from EA the development team worked in hellish conditions and the games creation was rushed in order to ship. This led to a final product that skipped over the usual quality testing phase Origin had always used in the past and launched in an unfinished and unpolished state with glitches and bugs making elements of the game unplayable. Large amounts of content had to be cut in order to make the deadline as well, angering Garriott who had always tried to ensure his Ultima titles featured expansive environments. Origin Systems did eventually release an official patch that makes Pagan far more playable than the original release, including features like targeted jumps, useful keyboard shortcuts, more forgiving item placement, removing the Avatar’s irritating tendency to fall down and hit his head after every other hit in combat, the total removal of all jumping puzzles (moving platforms now hover in place), and hundreds of major and minor changes largely inspired by fan feedback. Garriott (who was less closely associated with this title and delegated most of the work he would normally oversee to others) later explained “I sacrificed everything to appease stockholders, which was a mistake. We probably shipped it three months unfinished.”

Origin would later salvage what they could of the project in order to re-use its engine to power the game ‘Crusader’, which was considerably better received.

‘Chrono Trigger’ 1995

Concieved in 1992 by Hironobu Sakaguchi, the creator and producer of the Final Fantasy series in collaboration with his ‘rival’ Yuji Horii, the director and creator of the Dragon Quest series, and Akira Torijama, the famous manga artist behind Dragon Ball, Chrono Trigger is considered by many to be the pinnacle of the JRPG genre.

Travelling to America to research computer graphics, the three decided to do something that “no one had done before” and after spending over a year considering the complexities of coming together to create a new game they were contacted by Kazuhiko Aoki (then of Square) who offered to help produce it. The four met and spent 4 days brainstorming and writing down everything they wanted to accomplish with the game whilst Square convened a meeting of between 50 and 60 developers (including scenario writer Masato Kato, who would become the games story planner). The team began work on a time travel themed narrative and hoped to target the new Super Famicom Disk Drive system that Nintendo were developing with Sony, however Nintendo dropped the deal and partnered with Phillips instead before eventually backing out of making the system altogether. Square at the time were furious, reworking huge chunks of titles to fit onto carts instead of CDs and the scene was set for Square’s defection to Sony’s more powerful and promised CD based console, the Playstation once the 16-bit generation ended. The change to a ROM cart actually enabled Tanaka to find a way to seamlessly transition between battles and the field, which wouldn’t have been easy to accomplish on a CD based medium and helped the games flow immeasurably.

Sakaguchi would later comment that working on Chrono Trigger allowed both Square and Enix to work on a kind of title neither side would have been able to create alone. More serious and involving than the Dragon Quest series but lighter and more comedic than Final Fantasy. The games all-star development team produced almost more content than the SNES could handle, and beta testers reported that they wanted to play the game immediately again after finishing, prompting the inclusion of the first ever ‘New Game +’ feature included in a video game that allowed a second playthrough of the games narrative retaining levels and experience from the first, retaining a sense of accomplishment. This eventually led to the integration on multiple endings based on a number of factors including some dedicated to playing out after the player party dies. Chrono Trigger even offer the option for players to take on the final boss at various points in the early game, seriously affecting how the story plays out.

Chrono Trigger was primarily scored by Yasunori Mitsuda, with Final Fantasy composer Nobuo Uematsu contributing tracks as well. One track composed by Noriko Matsueda, a sound programmer at Square at the time who was unhappy with his pay and threatening to leave Square if he didn’t get the chance to compose music. Hironobu Sakaguchi suggested he help score Chrono Trigger, remarking, “maybe your salary will go up.” At the time of release the number of tracks and sound effects in the game was unprecedented, with the soundtrack spanning 6 discs on its commercial release. Mitsuda later wrote “I feel that the way we interact with music has changed greatly in the last 13 years, even for me. For better or for worse, I think it would be extremely difficult to create something as “powerful” as I did 13 years ago today. But instead, all that I have learned in these 13 years allows me to compose something much more intricate. To be perfectly honest, I find it so hard to believe that songs from 13 years ago are loved this much. Keeping these feelings in mind, I hope to continue composing songs which are powerful, and yet intricate…I hope that the extras like this bonus CD will help expand the world of Chrono Trigger, especially since we did a live recording. I hope there’s another opportunity to release an album of this sort one day.”

At launch the game was an immediate best seller in Japan with the PS1 and SNES versions shipping more than 2.36 million copies in Japan alone and 290,000 abroad. Frequently listed as one of the best video games of all time, regardless of genre, it has been reworked and re-released on Virtual Console, Playstation Network and PsOne, Nintendo DS, iOS and Android. A sequel on the Satellaview named ‘Rad‘cal Dreamers’ was devised as a side story to tie up loose story threads and resolve a sub-plot that had slipped through the original. A text-based game in format with minimal graphics and music it only ever saw a limited release in Japan but continued the theme of multiple endings. A more serious sequel saw release on the Playstation in 1999, Chrono Cross presented the theme of parallel worlds and shipped 1.5 million copies. Despite all those involved in the project stating that they want to make a new game in the series, no new entry has been announced.

‘Lufia II: Rise of the Sinistrals’ 1995

Released for the SNES, the original Lufia title ‘Lufia and the Fortress of Doom’ was the first game produced by Japanese development studio Neverland. Known in Japan as ‘Record of Estpolis’ the series would take its name from one of the central characters in its debut instalment and although she never recurred in later titles the name stuck. This first title opens with a band of heroes (Guy, Maxim, Selan and Artea) taking on a group of powerful villains called Sinistrals. It is quickly established that Maxim and Selan are a couple and have a child, and although the battle appears to be won the pair find themselves unable to escape with their friends and perish. The game would later skip 100 years to allow you to play as the descendant of Maxim and Selan and deal with the reappearance of the Sinistrals.

The first game did well in sales and was a moderate success, but the most impactful moments of its story were in the opening hour. ‘Lufia II: Rise of the Sinistrals’ was written and developed as a prequel to the original game, focussing on Maxim and his relationship with Selan whilst building up to the inevitable tragic conclusion that players had already experienced. The second game (releasing in 1995) features a number of improvements over its predecessor. Battles in dungeons are not random but can be avoided with enemies visible on the map, dungeons are full of clever puzzles that straddle the line between ‘Final Fantasy’ and ‘The Legend of Zelda’ in complexity and ‘capsule monsters’ can be caught and added to your party.

Lufia II also features has one of the most elaborate side quests of any 16-bit RPG: the Ancient Cave. This is a 99 level dungeon that’s set up in a manner similar to a Rogue-like. Your characters begin at level 1, with only a limited assorted of items. The levels inside are randomly generated, the layouts, enemies and item dispersements change every time you start the dungeon. While your party still gains levels and can find new equipment, they lose most of it if they leave or are defeated, and return back to their original state. There are, however, exceptions. Items found in blue treasure chests can be kept and used in the main quest. The same goes for items found in Iris chests, which are special equipment only found in the Ancient Cave. You can exit the dungeon and keep your items if you use the Providence item, which is found semi-randomly throughout the floors. The catch is that there’s no way to save, and dying will kick you right back to the entrance. It’s essentially a game within a game.

The Lufia series would go on to spawn a sequel on the Game Boy Colour. ‘Lufia: The Legend Returns’ which uses many of the same elements found in the optional dungeon, and one on the Game Boy Advance, ‘Lufia: The Ruins of Lore’, which is considered a side story to the main series but is in canon. A DS series reboot ‘Lufia: Curse of the Sinistrals’ was also produced that reimagines the Lufia II story and drastically alters gameplay was also produced. The reboot was greeted with mixed reactions by the Lufia fanbase, although selling well. Strangely a large chunk of optional character interaction was cut from the English language release, although remaining in the games data at the time.

Lufia II pushed the boundaries of what a game could offer in terms of optional content and rivals many more expansive RPGs developed today, with no space limitations to take into account. Unusually, the game received an independent translation from the American for Europe, allowing for fixes to dialogue and bugs that were reported in-game.

‘Tales of Phantasia’ 1995

Based on an unpublished novel by Japanese writer Yoshiharu Gotanda, Tales of Phantasia was produced by Woft Team, a subsidiary studio of Telenet Japan. Gotanda would work as the games sole programmer and drew heavily on Norse mythology along with the works of H.P. Lovecraft and Michael Moorcock to accommodate western fantasy and fiction into then games narrative. Although many changes were made to his original novel, Gotanda oversaw all changes to characters, locations and scenarios personally and worked closely with the games director Eiji Kikuchi to ensure that changes were for the benefit of the overall project. Characters were designed by manga artist Kosuke Fujishima who was well known for his work on ‘Oh My Goddess’ and ‘You’re Under Arrest’ at the time and would later work on ‘Sakura Wars’ as well as subsequent ‘Tales’ titles.

A short while into production Wolf Team split from Telenet Japan because of ‘poor experiences’ in working with them and sought a new publisher. After unsuccessfully targeting RPG juggernaut Enix they managed to secure a contract with Namco. Internal conflict within Wolf Team eventually led to the majority of staff breaking away to form tri-Ace as an independent development company.

Unusually for a SNES title, the game features voice clips that are used to bookend the title and throughout the course of the game in battles. An opening theme song was also incorporated and necessitated the use of a high-capacity 48 megabit cart. In order to record voice acting for the game that the SNES could handle a system was developed called the Flexinle Voice Drive, which enabled full recordings to be made. This became a key focus of the games press releases, and created a significant amount of media buzz around the games release. So too did the games ‘Linear Motion Battle System’ which saw characters do battle in real-time across a 2D plane, mixing special, ranged and close attacks of various kinds to deal with advancing enemy characters.

Although releasing too late in the SNES’ life to make much of a dent in the market, Tales of Phantasia was a hit on release and secured a sequel on the new Sony Playstation. Remakes of Phantasia on the Playstation as well as Game Boy Advance and iOS would also be produced, although none were as well received or fit as well as the original, using altered graphics or storytelling. The iOS edition was panned by critics for adding unnecessary In App Purchases (IAP) and increasing the difficulty of the game by pumping up monster stats and removing save points from dungeons to encourage players to buy them. At this time there are more than 16 titles available, not including side stories, sequels or spinoff titles, with more expected in the near future. In 2013 Bandai Namco shifted their focus onto bringing more of their titles into the western market, with considerable success.

‘Suikoden’ 1995

Whilst ‘Arc the Lad’ set the stage for the kind of grand epic that was possible on the new Playstation console, it was ultimately a 10 hour prelude game for the later, more ambitious sequel. Suikoden shares many similarities with Arc in that respect, being developed as a prequel to an already-planned second instalment, but it also manages to stand alone as a title that pushes the boundaries of the genre in its own right.

Developed by Konami Computer Entertainment and releasing on the Sony Playstation, Sega Saturn and Microsoft Windows, Suikoden was produced by Kazumi Kitaue and directed by Yoshitaka Murayama with artwork by Junko Kawano and music from no less than 5 musicians (Miki Higashino, Tappy Iwase, Hiroshi Tamawari, Hirofumi Taniguchi and Mayuko Kageshita respectively). Centred around the political struggles of the Scarlet Moon Empire, the game sees you take control of the son of a famous general who is destined to lead a revolution and unite to 108 stars of destiny, all under the power of a true rune.

Loosely based on the novel ‘the Water Margin’ (Shui Hu Zhuan), which is considered one of the four great novels of classic Chinese literature, Suikoden focuses gameplay on three different styles of play that come together to form a sizable whole. Normal exploration and battling takes a more traditional JRPG form and features and expansive world to explore, whilst duels between two characters take on a rock/paper/scissors style of combat where assessing and guessing what the other side will do next it key to victory. The third and final play type sees large scale warfare occur between two opposing armies and puts a heavy emphasis on the characters that the player has recruited into their army from the 108 possibly available to him/her. Defeat in these instances can lead to character dying permanently and losing the ability to unlock the ‘complete’ ending. Each ‘Star of Destiny’ also helps expand on the player’s home base area which develops from a ruin into a powerful base of operations throughout the game.

The Suikoden series puts great emphasis on the clash between nations, armies and politics, but manages to also make the experience deeply personal to the player by making the story center around a single character and his struggles to come to terms with adversity. Although 108 characters are included in the game, each of them exists to teach him something different about himself, and as such when elements of the narrative play out it binds the player very closely to the action on screen. The inclusion of permanent character deaths also helps to generate a sense of value in characters who otherwise may not see a great deal of use after their recruitment. That the series has (with one exception) kept to a single chronological timeline allows for each installment to subsequently strengthen those around them, making Suikoden a title that can be played first or last in the series and remaining relevant.

Save files from a cleared game in Suikoden can be imported into Suikoden II and again into Suikoden III, allowing for the unlocking of bonus content. This hadn’t previously been a possibility for games that saved onto their own carts in the past and is a feature that ‘Arc the Lad’ and other PS1 titles would put to good use throughout this console generation.

At the time of release Suikoden was considered by many to be the height of roleplaying on the Playstation, with an average score of over 80% in the magazines of the time. Game Informer ranked it the 82nd best game ever made in its 100th issue in 2001 and IGN labelled it ‘game of the year’. As the first instalment of a franchise, Suikoden was a massive success, and spawned a sequel that is debatably the best title on the original Playstation console as well as a legacy that has spanned iterations on other devices. More recently the Suikoden series was released onto Playstation Network for the PS3 and PSP, allowing those previously unable to purchase the game outside of Japan (and a limited western production run) to finally experience it, leading to a second boom in interest in the series.

Overall

RPGs are beginning to really hit a ‘golden’ period in their history in the mid-90s with the release of two games that have come to define the Super Nintendo’s catalogue. ‘Final Fantasy VI’ is considered to be one of the best that its huge series has ever produced in terms of story and characterisation, whilst ‘Chrono’ Trigger is the kind of legendary title that’s almost impossible to replicate and brought together all of the biggest names in the genre to produce a ‘killer app’ for the system. Meanwhile new faces are beginning to push their quality and rival Square and Enix in terms of RPG output. ‘Breath of Fire II’ features some of the best sprite work on its system whilst ‘Lufia II’ puts a monster catching mechanic to good use alongside prequel storytelling that subsequently makes its original title even more interesting. ‘Tales of Phantasia’ incorporates human speech onto a SNES cart whilst ‘Terranigma’ is a debate on creation and the nature of god all in of itself.

Western releases are comparatively slower and although possessing some equally powerful titles, are beginning to show a dip in quality. Despite a bumpy production period, ‘Shadowrun’ managed to prove that pen and paper gaming has a place on consoles and managed to keep the quirks of its unique setting intact making the transition. Ultima produced its darkest and most adult title in ‘Ultima VIII: Pagan’ and sets the stage for the company to move into an all-new area in the series’ next iteration, however constraints put upon Origin by EA led to an ultimately flawed title that even the team weren’t proud of. ‘Wizardry VI’ meanwhile was beginning to show the cracks in the series armour, failing to capitalise on the graphical prowess on desktops at the time and being outclassed by consoles. Failing to target a successful western audience, the series begins to target the Japanese fan base instead. Frequently past glories such as ‘Might and Magic’ and ‘Wizardry’ were bundling titles as trilogies for re-release.

With the Playstation emerging onto the scene, Sony’s console begins to turn its attention to the RPG, with initial title ‘Arc the Lad’ serving as a bite sized portion of what was to come. Graphics are becoming sharper and larger sprites that can emote are becoming the standard to allow for better storytelling. More complex narratives with adult tones are starting to make their way into titles on consoles as well as those on desktop computers, sparking some debate as to if these games should be targeted at children and the nature of censorship.

Ultimately the divide between RPG production in the East and West appears to come down to the difference between companies fostering and encouraging the talent of those who work for them. It’s difficult to believe that the same year that produced ‘Chrono Trigger’, the gaming equivalent of an all-star line-up of JRPG development, and ‘Ultima VIII’, which saw EA squeeze Origin until they simply couldn’t produce the game they wanted to make. Sadly, whilst the JRPG and various sub genres would continue to rise in popularity, the WRPG was about to hit on hard times, and lessons at EA would not be learned, leading up to one of gaming’s most disappointing titles.