‘Pool of Radiance’ 1988

The first title in a series of four to be developed and published by Strategic Simulations Inc (SSI), Pool of Radiance was the first official adaption of TSR’s ‘Advanced Dungeons and Dragons’ property, which had been the foundation of many of the early concepts leading into the RPG genre. Sharing a chronology as well as the same game engine, the ‘Gold Box’ series (named after the Gold Box Engine and the golden coloured packaging in which these games were sold) were phenomenally successful in the west.

After seeing the success of the Ultima series, TSR offered its license to game developers with 10 companies applying for the exclusive contract. SSI president Joel Billings seized the opportunity to capitalise on his company’s experience with war gaming simulations and outlined a broader vision for what could be accomplished with the rights than the competition. The development of the Gold Box engine and its original games was then entrusted to Chuck Kroegel and George MacDonald who quickly realised that they had to draw heavily from the original source in order to stay true to the license. This included drafting experienced campaign writers.

With a scenario created by TSR designers Jim Ward, David Cook, Steve Winter and Mike Breault the game maintained the official narrative clout to live up to the D&D title, with a small section of the D&D world developed specially for the game to take place inside so as to avoid clashing with existing campaigns published by TSR. SSI concentrated on adapting the dice based rules and mechanics of AD&D into a working model, with the random nature of rolls often causing trouble at first. Graphic Artists were given copies of the existing monster manuals and adapted faithfully content found within, artists Tom Wahl, Fred Butts, Susan Halbleib and Darla Marasco also state that they took inspiration from the Unearthed Arcana published sourcebook of the time.

Like a game of D&D, the player starts by constructing a party with race and class taken into account before the computer randomly rolls statistics for them. Appearance could then be customised or a pre-generated party could be selected. A max party of 6 characters with two empty slots for guest NPCs was allowed, bringing the maximum party to a total of 8. Exploration in the game takes place in the first person, with party stats and descriptive text on screen at all times. In combat however the game shifts to an overhead, turn-based combat system not unlike those seen in the Ultima series, with combat options decided by character class. Experience and currency collected through random encounters could then be used in towns to train and purchase new equipment.

Set in the Forgotten Realms in a city known as Phlan, the party quickly establishes that the city has begun to fall into a decaying state and that only a small section of it is inhabited by Humans. Tasked with helping to rebuild the city the council recruits the party to drive monsters from the neighbouring ruins. Eventually this mission grows to encompass a wider area outside of the city walls and this leads to the revelation that an evil spirit named Tyranthraxus has taken possession of a powerful dragon and that he must be defeated to keep the city safe. The city itself is fairly expansive, with a ‘New Phlan’ area where the wealthy live and a slum for the down on their luck, political upheaval and bickering amongst the ruling factions is also to blame for the city’s current state.

Released in the summer of 1988 on the Commodore 64, Apple II and IBM PC, the game shipped with a 28 page booklet and inside a golden box. A 38 page Adventurer’s Journal containing the games background was also included, as well as physical flyers and maps. Altogether this was one of the most extensive boxed games produced and the quality was deliberately pitched to a high grade by SSI in order to impress TSR with their use of the license. A novelization of Pool of Radiance was also produced and published by TSR, written by James Ward and Jane Cooper Hong. It spawned an additional two sequels in this format in the novels ‘Pools of Darkness’ and ‘Pool of Twilight’. Despite being compared to other games from which the design and format had taken inspiration (Wizardry, Might and Magic, Ultima) the title sold extremely well. Sequels ‘Azure Bonds’, ‘Secret of the Silver Blades’ and ‘Pools of Darkness’ soon followed, spurring on rapid growth of SSI as a company.

‘Dragon Quest III’ 1988

‘Dragon Quest II: Luminaries of the Legendary Line’ was released by Enix within a year of the original title’s launch to capitalise on its success. A better game than the original in all respects, it included all of the advanced features of the Dragon Warrior release and considerably more content. Like the original, it too saw western release as Dragon Warrior II, and although undergoing censorship to meet Nintendo’s standards for the time the game was a success. Sadly whilst concentrating of fixing mistakes found in the original, the second title never made massive headway into new territory. It was with the release of ‘Dragon Quest III: The Seeds of Salvation’ that the series would go from popular to national treasure overnight.

A prequel to the original Dragon Quest, and the concluding part of a loose initial trilogy, Dragon Quest III expanded upon its predecessors by including a larger open world and non-linear gameplay with the addition of a persistent day and night cycle, the ability to change classes and a stronger focus on story to compete with the Final Fantasy series. As with Dragon Quest II, the core team of Yuji Horii, Akira Toriyama and Koichi Sugiyama was reassembled to work on the third instalment in the series, which has been growing in popularity in Japan. Nobody however could have predicted how popular this third title would be.

Dragon Quest III sold over one million copies on the first day of sales in Japan alone, with police making 300 official arrests for truancy among students who had abandoned school in order to purchase the game at launch. In total 3.8 million copies were sold in Japan, sparking the tradition that Dragon Quest would launch over a weekend, with one discredited theory suggesting that the Japanese Government requested this of Enix so as not to disrupt school and workplace productivity.

At the games outset the player begins as a single Male or Female hero, although as the quest goes on a team of player created party members can be recruited from the Tavern. This team can be made up of multiple classes in either male or female forms, including Wizards, Fighters, Soldiers and Goof-offs. Class changing can be done at the Temple of Dharma, whenever a character other than the hero reaches level 20. It has the negative effect of reducing that characters level to 1 but allows him or her to keep all skills learned by the previous class. This allows for multi-class characters making up a party of the players own design.

A fiend by the name of Baramos threatens to destroy the world and the son or daughter of the legendary hero Ortega is tasked with saving the day. Accompanied by a party of the players design, the narrative soon sees Baramos revealed to be an agent of the greater threat Zoma, who frequents the Dark World. The games narrative takes itself on a town-to-town romp where local problems are solved through fetch-quests and occasional dungeon exploration in order to unlock new areas to progress into, a formula that Dragon Quest keeps to this day.

A remake of the NES edition of this title was later devised for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES) that utilised the higher graphical prowess of the new console to upgrade the game significantly. Never released outside of Japan due to Enix America’s closure in 1995, it only ever received an unofficial translation into English. A remake for the Game Boy Colour based on the SNES version did however make its way into the west and due to the reinstatement of content cut from the NES release earned the first ‘Teen’ rating on the Gameboy. A new class was added to this edition, as was the ability to customise character stats with seeds when they were created. A board game minigame was included as was the medal system seen in later Dragon Quest instalments post IV. Players could trade medals via link cables with special medals being earned for defeating set totals of monsters. The biggest addition however was a pre-game sequence that sees the player undergo an Ultima-like test of character that decides their initial stats. Sadly the SNES remake was used as the foundation of the iOS and Android editions of the game, so these features never made it into the most recent ports.

‘Final Fantasy II’ 1988

Initially Final Fantasy II was something of a directionless game that underwent a prolonged development cycle. With no obvious ‘sequel’ to the original games story the decision was made to strike out in an all-new direction, with none of the original games characters of locations revisited. Hironobu Sakaguchi, who had served as main planner for Final Fantasy, assumed to role of director and took on a much larger development team. Seeing that the strength of the original game had been its story, with other elements implemented around it, he placed the focus of the sequel on building a dramatic and compelling narrative.

Whilst Sakaguchi outlined a rough plot for the title to follow, the actual scenario was written in detail by Kenji Terada. Nobuo Uematsu returned to compose the distinctive music and Amano served as concept artist. Their task, to create something similar to Final Fantasy but unique in concept. As he had on the original title, Nasir Gebelli worked on programming the game, but when his visa expired he was forced to return to California. Rather than lose him the rest of the development staff moved the project to Sacramento along with the necessary equipment for him to finish working on the game there. Eventually the title was released one day shy of a year after the original had been released.

With an increased focus on character development the player was put into control of a party of four characters. The main hero Firion, friend Maria, soft spoken archer Guy, a conflicted dark knight named Leon would all also be joined by guest characters who would appear and leave as the plot demanded it. Each character undergoes a personal journey of some manner over the course of the game, with Leon switching sides from hero to villain and finally back to hero before the credits rolled. Great care was taken to make the characters feel human and not like the super-heroes of other contemporary titles who took world altering events at face value. Death scenes for some guests also served to add emotional impact and comic relief was introduced to balance this out. An English language version was produced at the time but ultimately never saw the light of day, with the key reason being that Square wasn’t sure that the story could be adequately translated into English without losing its subtlety. Western players would instead have to wait until the Playstation release of ‘Final Fantasy: Origins’ to experience it for themselves.

Gameplay in Final Fantasy II takes on a significantly off-book approach to levelling, with characters not using experience points but instead gaining stats according to what they do in battle. Characters using swords gain mastery over that weapon, with those who take damage increasing their defence or health. Magic spells get more powerful as they are cast whilst MP reserves are expanded through casting frequently. On paper it sounds like an extremely logical and sensible approach but in practise it makes the game very difficult to master and sees players having their party attack themselves in order to push their HP higher. The game also uses a system to remember key plot points and ask NPCs about them later, which has not been seen again but works extremely well as a narrative device. Character Cid and the concept of the Chocobo also make their first appearances in Final Fantasy II, going on to become series staples. The focus on narrative greatly helps the game to stand up today despite the complexity of the games levelling system, with the story remaining an interesting experience and even being referenced in more modern titles such as Final Fantasy IX and the Kingdom Hearts series. A Manga series was drawn to accompany the game and serialised as well as a novelization written by scenario writer Kenji Terada and published by Kadokawa Shoten under the sub-heading ‘Labyrinth of Nightmares’.

At present there are 14 ports of Final Fantasy II, with Square Enix constantly shifting the original Final Fantasy and its sequel onto new hardware with altered graphics to keep them looking relevant in the market of the time. At launch the original NES (Famicom in Japan) version sold 800,000 copies. Including the re-released versions this title has shipped in excess of 1.28 million copies worldwide. Despite these high sales figures it is considered the lowest selling instalment in the Final Fantasy series but sold enough to guarantee sequels almost immediately. Upon release review scores across the board were solid 9s and 10s, although historically the systems it introduced were deemed mistakes and never used again, the game however remains in the top 100 iOS RPGs on the iStore several years after release.

Final Fantasy III would go on to return to the more traditional levelling system and reintroduce the concept of a player drafted party of adventurers, adding a job-change system but keeping to the new series mantra that story be placed front and centre for their games. Whilst the whole team from FFI and FFII came back together to produce it, this game too never saw a western release due to the recent shift at Nintendo to support for the SNES console and fans had to wait for a 3D remake on the DS to enjoy it. At launch the game sold extremely well on Japan however, and allowed for development of Final Fantasy IV to take place on the new SNES.

‘Wasteland’ 1988

A science fiction RPG developed by Interplay Productions, Wasteland was published by Electronic Arts for the Apple II (which was on its last legs by this point, having seen Richard Garriott announce that Ultima V would be the last Ultima title developed on the aging hardware), DOS and the Commodore 64. Set in the United States of America in the aftermath of an apocalyptic nuclear holocaust that has seen large areas of the earth’s surface irradiated and has made life a constant struggle for survival.

Set in the year 2087 following the devastation of a global war in 1998, a team of desert rangers is assigned to investigate a series of disturbances in the Southwestern United States, exploring pockets of Human civilisation that includes a ruined Las Vegas. Although initially a simple mission the game builds tension by placing evidence of a larger threat in the player’s path, eventually revealed to be a rogue AI operating out of a military base that is trapping and turning survivors into cyborg weapons. The game takes great pleasure in directly basing itself off of underground pen and paper hits such as ‘Tunnels and Trolls’ and ‘Mercenaries, Spies and Private Eyes’ created by the games designers Ken St. Andre and Michael Stackpole. Characters encountered have their own statistics that allow them to use different equipment and players can take a number of different approaches to situations based on what best suited their character builds.

In control of an initial party of 4, though your numbers can swell to 7 through recruitment of monsters and NPCs in the wastes, the game progresses unlike any RPG of the period with NPC behaviour governed by their own crude AI (sometimes making an excuse not to join you, others jumping into the party happily) and delighting flowery descriptive prose such as ‘explodes like a blood sausage’, prompting a PG-13 label to be added to the game in the USA. Wasteland is a punishingly difficult title to complete with difficulty factored into puzzles, and the environment instead of simply the enemies you face.

Featuring a persistent world, where changes to the game were stored and kept, returning to an area later in the game could lead to the player finding it drastically altered from the condition in which they had first found it. Hard drives were rare in home computers at this point, meaning that the persistent changes of this kind were a rarity compared to instantly resetting environments. Changes were made on the game disc itself to account for the lack of hardware available, prompting players to make multiple copies of the disc in order to see different changes. In order to preserve space to enable this on the disc some story elements were relegated to a printed booklet that came with the game and needed to be read by the player when the game prompted. This also acted as a crude form of copyright protection.

After a heavy five-year development period, Wasteland was praised for its ease of play, richness of plot and problem-solving. Computer Gaming World reviewed the game not once, but twice (a second time in 1991) citing the way in which NPCs related to each other and the player coupled with hard choices with cause and effect made for gripping gameplay. It received the Game of the Year award in 1988 and was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1996, being rated the 9th best PC game of all time. In 2000 Wasteland was ranked 24th top PC game by IGN who called it “One of the best RPGs to ever grace the PC” and “truly innovative for its time”. A sequel, titled ‘Fountain of Dreams’, was released set in post-war Florida but none of the creative team from Wasteland were involved and EA decided to not advertise it as a sequel for that reason. Interplay themselves produced a game named ‘Meantime’ which used the same engine and setting, but it was not a continuation of the narrative started in Wasteland. The game was cancelled when the 8-bit market went into sharp decline and the 16-bit era dawned. Spiritually, both Fallout and its immediate sequel Fallout 2 stand as Interplay-led successors to the Wasteland title, with the inability to reclaim rights for the name from EA leading to the creation of a new IP.

‘Curse of the Azure Bonds’ 1989

The second title to appear in the Gold Box from SSI was ‘Curse of the Azure Bonds’, which followed chronologically from ‘Pool of Radiance’. Launching as a game, prequel novel and campaign simultaneously in an early example of cross-media marketing.

Like Pool of Radiance before it, the game ran on the Gold Box engine and saw a player created party of 6 characters (aided by two NPCs) tackling the games tasks. Player parties from the previous title can be imported into Azure Bonds, but a copy of Pool of Radiance was not essential to play the game, unlike the Wizardry series. Characters can also be transferred into the title from a game called ‘Hillsfar’ which also took place inside the AD&D setting but took a more action/adventure orientated approach to the license. New classes in the form of the Paladin and Ranger are added to the games system to bring more diversity to the party, and multi-race hybrid characters can now be included such as half-elf or gnome characters. Due to the sequel-like nature of the game the decision was made to keep the challenge level high as most players would import an established party, and 25,000 experience points were awarded freely to all new characters created to balance out this challenge. Visually the game looks very similar, with assets reused throughout but new monsters and locations added to the mix to bring more variety. Reused assets received a slight graphical upgrade to make up for their reappearance.

New features added to the game include an overland map which allows players to quick-travel to new or previously explored locations, an act which may trigger a random encounter on the journey. A ‘Fix’ command was added to the list of actions available to the player in camp which allows for characters to restore health more quickly as long as a Cleric or Paladin is a part of the group. These in addition to the new classes and locations made the sequel extremely appealing to players of Pool or Radiance.

The games story follows the party as they wake from a magical sleep in the city of Tilverton, their possessions stolen and their memories of the past few days wiped away. Each player has five blue-coloured tattoos on their arms called ‘bonds’. Local sages inform the group that the bonds represent five different evil factions, and that through them these factions can control the party. A brush with a royal carriage and encounter with the Fire Knives removes one, and the party decide that the best course of action is to topple these evil factions in order to free themselves. Alias and Dragonbait, a female warrior and loyal Lizardman companion can join the party on their quest (and are the central characters in the Novelization which would spawn a trilogy around them) as NPCs and through a series of adventures the party will discover that original game villain Tyranthraxus in the form of a Storm Giant controls the last bond. After a thrilling battle against him the game ends.

Reception for Azure Bonds was overwhelmingly positive, with people praising the new additions to the gameplay and citing that it felt more like Advanced D&D than Pool of Radiance ever had. As a self-contained title it was well received, but as the second instalment in a series with two more entries to look forward to it was a certified success. ‘Secret of the Silver Blades’ was released a year later and continued where the title left off.

‘The Final Fantasy Legend’ 1989

Also known as ‘SaGa: Warrior in the tower of the Spirit World’, The Final Fantasy Legend was Square’s first game to top 1 million units shipped abroad on launch and the first portable RPG ever created. Conceived by Nobuyuki Hoshino and developed under the direction of Akitoshi Kawazu, it targeted a very unique new market.

Until the release of Nintendo’s Game Boy handheld, gaming had been bound to a television set or desktop computer. Now that a more mobile system was on the market Square was looking to create a version of the RPG genre that would be enjoyable on the move, capable of being played in short bursts and easy to control with the simple input that the Game Boy allowed. Akitoshi Kawazu, who notably was responsible for the game design on Final Fantasy and Final Fantasy II (in particular the strange levelling system seen in the sequel) was tabbed as the man for the job by Hoshino. Initially instructed to create a game that would “have the same appeal as Tetris”, Kawazu and Koichi Ishii focused their development process into the creation of an RPG, which they felt was the company’s strongest asset.

Given a target that the game should be able to be completed in 6-8 hours from start to finish (the average aeroplane flight between Japan and Hawaii) developers sought to optimize the game for short bursts of gameplay. Square raised the encounter rate of random battles from a lower standard as demonstrated in the Final Fantasy series to date in order that players would be able to quickly battle a selection of different monsters in a short period of time. Designed to be difficult and feature advanced gameplay systems, Kawazu began to add new ideas of his own to keep gameplay deep and interesting without requiring too heavy a learning curve. Meat ingestion by the Monster class as a way to learn enemy abilities was the crux of this plan, as was equipping gear to Humans and randomly gaining stat boosts for Mutants. They proved harder to successfully implement than originally intended but by the third Game Boy installment were excellent.

The graphics of the game were designed in black and white in order to better interface with the monotone screen that the Game Boy possessed, with Ryoko Tanaka designing background graphics and producing concept art for the games sprites. Nobuo Uematsu produced 16 tracks for the title that would work on the hardware, taking advantage of the stereo option and unique waveforms that produced only three notes. The 2-Megabit capacity of a standard Game Boy cart for the time took a heavy toll on the games more epic ambitions, cutting much content before it could be properly implemented. Turn based combat, saving the game, multiple classes of character and levelling were all included in the final game however, as was an overworld to explore.

The original Game Boy bersion shipped 1.37 million copies worldwide (1.15 million in Japan) and Square quickly released two sequels, adding the Final Fantasy title outside of Japan to help sell the otherwise new IP through brand recognition. A tactic that Square would return to again in the future. Remakes on the WonderSwan Colour, mobile phones and Android have also sold well, with the SaGa series going on to produce a total of 12 entries to date on handheld and console.

‘Phantasy Star 2’ 1989

At the time of its release, Phantasy Star II was one of the largest and most expansive RPGs available and arguably the hardest game ever made for the Mega Drive. Although translation issues prevented the game from receiving a world wide release, an English and Japanese version was available. Tectoy later translated the game for the Portuguese and Brazilian markets, and Samsung worked on a Korean version. Due to the games perceived difficulty at Sega, the game released with a 110 pages hint book in the UK and US markets.

Tooru Yoshida, the games Graphic Designer has spoken often about how the game was originally intended to feature the character of Lutz from the original Phantasy Star as a protagonist, however the development team felt that he had come across as a somewhat weak and undefined character in that title and might make for a bland central figure. Once the decision was made to move away from using him and developed the character of Rolf (Yushisu in the Japanese release) the main writer and director of the title Chieko Aoki changed significant chunks of the story as well. Previously the plan had been to send Lutz back in time to help Alis (the player character in Phantasy Star) in her quest, but Aoki disliked the idea of re-writing the games own timeline and felt that players of the original may resent changes to what they’d already accomplished, and so began changes to suit a new character instead. A sequence where a native people named the Motavians underwent a form of genocide was also cut.

Originally planned for release on the Sega Master System, Sega shifted their attention to the Mega Drive with the launch of their new console. The team had to rework substantial amounts of the games programming and had to reduce their play-testing and debugging period by over half in order to get to grips with the newer changes between platforms. The team credit Yuji Naka for making it possible to release the game at all given the reduced working time. Graphically the game received a few additional colours to make use of the extended palette that the newer system was capable of producing, but the 8-bit feel of the game still remains with smaller, simpler sprites. This may have led directly to Sword of Vermillion being green lit to lead Sega’s new marketing campaign in place of the larger and more impressive Phantasy Star II. Unusually for the time, every member of the team working on Phantasy Star II were capable of producing graphics and they quickly split the workload between them into ‘Main’ and ‘Sub’ graphical roles. Hitoshi Yoneda was also brought in to paint the distinctive cover and artwork that the games production materials made use of in Japan.

Players of Phantasy Star II will remember that the dungeons in this title were extensive, huge and easy to get lost inside. Much of the key game is spent navigating these massive environments and whilst the bulk of the team were working on systems, graphics and creating a narrative, the task of creating the dungeon layouts was given to a new employee who – in the words of game designer Kotaro Hayashida “put a ton of effort into the maps and kind of overdid it.” Whilst beautifully crafted they do unbalance the game in its later half, and Chieko Aoki included them with mixed feelings.

Though hard to beat, players loved Phantasy Star II at launch and the game was successful enough to spawn work immediately on a sequel. Phantasy Star III chose to focus on a generational story set within what appeared to be a traditional fantasy world, eschewing any of the Phantasy Star series trappings well into the last quarter of the game. Playing very traditionally for an RPG of the time it was received with mixed reviews but did contain an excellent twist ending to better tie it into the series and several innovations. Battle scenes contained parallax scrolling background on multiple layers and the game used a generation by generation system where the love interest of the main character’s choice bore the next playable protagonist, leading to higher replay value. None of the staff of Phantasy Star II returned to make Phantasy Star III, however many would return for Phantasy Star IV, which would see release in 1993 and become the best received title in the series.

Phantasy Star II has been ported from the Mega Drive to various collected editions of the Sega line, as well as being packaged with the other Phantasy Star titles onto a Gameboy Advance cart and remade for a Japanese only Playstation 2 edition. Today it can easily be found in digital format across all major systems, although Sega has pulled it from the iStore.

‘Sword of Vermillion’ 1989

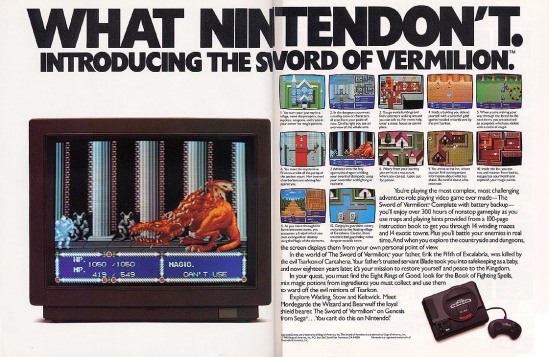

As the launch of the Mega Drive (Genesis) approached, Sega began an advertisement campaign that was aimed at turning players off of the growing Nintendo market that had dominated the last generation, and focused on giving people something new. Sword of Vermillion follows the adventures of the young son of Erik, king of Excalabria who having been smuggled out of his kingdom’s destruction takes on a quest to defeat the evil Tsarkon as part of a mission handed to him by his adoptive father on his death bead. Poised at the forefront of Sega’s visceral advertising campaign ‘Genesis does what Nintendon’t’, Sword of Vermillion was designed to show off the power of their new console as well as the depth of colour that it could display. Subsequently it found itself featured heavily in adverts at the time.

Packaged with a 106 page hint book in the USA, the game featured a variety of different styles that were popular at the time and served almost as a technical demonstration of what other games would be capable of on the console than a linked vision for a title in its own right. Town exploration was done from an overhead viewpoint similar to that seen in the Dragon Quest series, whilst leaving and entering a dungeon would trigger a first-person perspective. Battles took place from an overhead angle in a real-time environment where the player needed to dash around and swat at monsters whilst avoiding being hit, and Boss encounters took on a side-scrolling perspective of the same system. In comparison to the single, more carefully crafted viewpoint seen in Phantasy Star II or III on the same console (released either side of Vermillion), it was a confusing mess of a game.

Sword of Vermillion was designed by Yu Suzuki and his team ‘AM2’, their first console game after a string of arcade titles such as ‘Space Harrier’ and ‘After Burner’. The soundtrack was composed by Hiroshi Miyauchi, a frequent collaborator with AM2, whose work on Sega games at the time was incredibly prolific. Expectations at release were for an action themed RPG that played to the strengths of the team’s experience and many were surprised at how slowly the game was paced, with basic progression requiring concentrated effort. Dungeons appear as pitch black screens without buying candles, and without a map the auto-map wouldn’t function. Actions required the use of a mini-menu in the vein of the original Dragon Quest and even opening a chest wasn’t enough to collect items, they had to be then collected using a separate command. What could have been the beginnings of a powerful new franchise under Sega’s belt instead remained a failed experiment, though as a technical demonstration it worked wonders.

Despite being poorly received at the time, Sword of Vermillion has made its way onto several compilations such as the ‘Sega Genesis Collection’ for Playstation 2 and PSP (although it was one of the few titles omitted for the Ultimate Collection on Playstation 3, bumped for the Master System original Phantasy Star game). It’s also seen digital release on Steam and the Wii Virtual Console.

Overview

This generation of RPGs took risks not associated with those that came before them. Square proved in Final Fantasy II that putting extensive time and effort into a wholly original take on the concept of levelling characters could backfire dramatically, whilst aiming their SaGa series at the Game Boy proved to be a massively popular decision. Enix discovered that the genre had evolved into a cultural phenomenon which exploded into a massive sales boom for Dragon Quest III, bringing a hype to the JRPG that hadn’t previously been experienced elsewhere. Meanwhile in the West games like Wasteland were experimenting with concepts such as persistent worlds and cause and effect.

Dungeons and Dragons, which for a long time had been a major inspiration for the genre entered the scene with a smash, delivering not one but two titles in the Gold Box series that represented a high standard of writing and further established that freedom to explore and create original characters fuelled the WRPG sub genre. Sega meanwhile gambled on Sword of Vermillion being as much of a hit on their new Mega Drive console as their Phantasy Star series was on the Master System, but ultimately didn’t manage to capture the same imagination that the sister series possessed.

8-Bit systems are giving way to newer and more powerful consoles and games are starting to have to take into account the platform of their development in a manner not seen before, as porting becomes a harder task and larger financial risk. The Apple II, NES, Master System and other older systems would hang on for several years before finally disappearing, but original titles would soon dry up in favour of sub-standard ports from their successors.